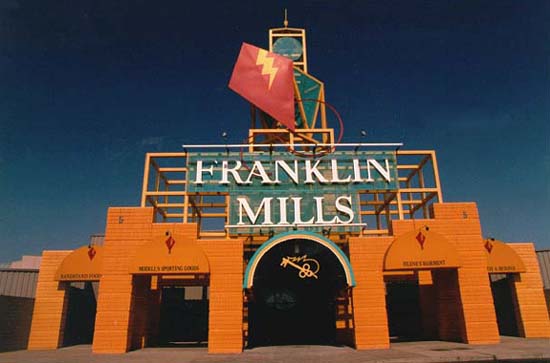

How Franklin Mills became

an economic powerhouse

A decade after its ground-breaking, Franklin Mills has become a tax-paying, job-creating business center luring shoppers

from around the world.

By David J. Foster

Staff Writer

It was a gamble.

The City Planning Commission, all-too-conscious of the difficulty attracting business to tax-choked Philadelphia,

recommended turning the defunct 288-acre Liberty Bell racetrack, Knights and Woodhaven rds., into a new community of

6,000 to 10,000 housing units encircled by three mid-sized apartment complexes.

The problem? "They weren't proposing new libraries, schools, or recreation centers," said City Councilman Brian

O'Neill (R-10). Residents from surrounding Parkwood and Millbrook balked.

At least a mall could be controlled and self-contained. Its owners could negotiate, compromise, and, in

job-starved Philadelphia, dump cash into local coffers.

"I (wanted) the kind of light manufacturing the city lost over the years," said City Controller Jonathan Saidel. "I

was just hoping it would break even, that we'd get a few jobs."

Watching crews demolish the track's grandstand, optimistic Parkwood resident Jack Jackoway told reporters he

expected "half the community" to be working there.

Instead, half the employees manning the Franklin Mills mall would reside in the surrounding neighborhoods.

When Western Development (now the Mills Corporation) moved in with $300 million and the promise of 2,000

construction and 5,000 permanent jobs, city officials salivated. "It (reversed) a trend of building regional facilities outside

the city, forcing people to leave the city to do their shopping," said Chris Cashman, then deputy commerce director.

O'Neill, citing Western's promise of $1.6 million in community development, called it a "victory for the people"

and the city.

A decade later, O'Neill's boast no longer seems hyperbolic as Franklin Mills, with $300 million in annual sales,

has grown into an economic engine as Philadelphian as the soft pretzel and just as lucrative.

"I never expected it to bring in so much revenue," said Saidel.

Tops in tourists

Independence Mall draws 800,000 visitors annually, the Franklin Institute 900,000. The Liberty Bell, our most

popular historic site, attracts 1.5 million.

Franklin Mills?

18 million.

It allows the Mills Corporation to tout the mall as the state's top tourist attraction.

The figure is based on the number of vehicles that enter the mall's grounds- almost eight million last year- and

multiplying that by 2.3, the average number of people in each car.

"If you adjust for employees and people taking a shortcut through the center, you're talking about 16.5 million

people," said mall manager Peter Bergum.

The formula also undercounts the 4,000 busloads of national and international tourists dropped off for five to

eight hours of outlet and off-price shopping.

For tourists, greeted on arrival by mall mascot Amos the Mouse, Franklin Mills is a consumer theme park.

Monitors blare music videos; a giant red, white, and blue mechanical bust of Benjamin Franklin spouts the time and Ben's

most popular sayings.

Servers at the Franklin Mills Pizza Hut struggle to interpret English broken with German, French, and Polish.

This summer, 700 Kuwaitis stormed Nordstrom Rack and Off 5th:Saks Fifth Avenue Outlet. They joined consumers from

Japan (23 busloads so far this year), Israel (5 buses), Hungary (5 buses), Thailand (3 buses), Laos, Denmark, Sweden,

Belgium, Turkey, Canada, Russia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

Brazilians (the most frequent international shoppers with 40 busloads this year alone) stock up on jeans and

electronics, which cost four times as much back home. "On Saturdays during Christmas stores are emptied," said Bergum.

"Some people buy suitcases to take their purchases home."

Overall, visitors from 26 countries have made Franklin Mills a stop on their American journey. Most fly into

New York and make a half-day stop before rolling on to Washington D.C. "They are committed to spending time and

serious dollars," Bergum said, from a minimum of $250 to as much as $1,000. "They are our best shoppers."

"My goal is to get them to stay overnight," said Rose Leone, the mall's tourism director. Eight area hotels offer

discounts to anyone who says they are shopping at Franklin Mills. Leone has also partnered with area restaurants. Among

the most popular stops, the all-you-can-eat Old Country Buffet in Bensalem and Bookbinder's, which offers tourists early

bird discounts.

"We are encouraging them to see the rest of the city and spend their dollars here," Leone said.

A notch above

It was a different story during opening week in May 1989. By noon each day the grounds choked with 10,000

local vehicles. They came to experience off-price outlet shopping in a way unavailable anywhere in the Delaware Valley:

Enclosed and air conditioned.

"Franklin Mills moved (discount shopping) up a notch by offering the amenities," said Bergum. The closest

competitor was its sister and prototype, Potomac Mills, attracting 250,000 shoppers weekly outside Washington D.C.

Nestled alongside I-95 south of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, Franklin Mills proved adept at luring motorists, who

turned I-95's Woodhaven Rd. exit into a parking lot.

It confirmed the community's worst fear and became the mall's first test. "They wanted to know how we were

going to improve the roadways," Bergum said.

In truth, the Woodhaven Rd. exits were treacherous long before the mall. Acceleration lanes were single and

short, snarling rush hour traffic. Western offered the state $2 million in matching funds to pay for the upgrade.

Though PennDOT eventually carried the cost (allowing Western to use the $2 million to complete mall

construction during the crippling 1990-91 recession), it was Franklin Mills' arrival that prompted work on the stalled

project. "And traffic along Woodhaven has never been better," O'Neill said.

The mall did pay for a ramp reversal on Woodhaven Rd., improvements to roads encircling the mall property, and

new traffic lights, which the Mills Corporation maintains at a yearly cost of $75,000 to $100,000.

Then there's the $3,000 check mailed annually to Bensalem Township to pay for maintenance on a traffic signal

on Rt. 13. "We agreed the mall altered traffic patterns on the highway and the lights were necessary." Sources said it was a

gesture of good will to the neighboring township. As one official put it: "Everyone got a slice."

Jobs and taxes

The biggest "slice" goes to the city.

The mall's 1996 Real Estate tax bill: $3.9 million. Its Use and Occupancy tax liability: $1.8 million. The

Business Privilege tax paid by its 200 tenants: Estimated in the hundreds of thousands.

"The city now has a major tax base, from property taxes to wage taxes, and it doesn't really have to spend any

money there," said O'Neill. "Franklin Mills repairs its own streets, fixes its own lights, removes its own snow, and has its

own security. It's pretty self-sufficient."

Sales tax revenue contributed to the city by Franklin Mills shoppers is difficult to calculate as clothing outlets

dominate the mall. Clothes are not subject to the six percent state or one percent city sales tax. (Leone is designing an

out-of-state ad campaign promoting Pennsylvania as a tax-free zone for clothing.)

Still, with half the mall's visitors living outside the city, close to nine million people are paying sales taxes at the

food court, Phar-Mor, Suncoast Motion Picture Company, and the Encore Books Outlet. Bergum's assessment: Between

$75,000 to $80,000 paid to the city annually.

Then there's the wage tax.

Philadelphia's ongoing job hemorrhage cripples city finances by chasing younger residents into the suburbs and

reducing city income. For every $20,000-a-year job lost, $1,000 in wage tax revenue disappears.

Franklin Mills employs on average 3,500 workers. That does not include the businesses that sprouted around the

mall.

Most significantly, in 1995, 43 percent of the jobs were held by residents living in the surrounding 19154 and

19114 zip codes.

"They're not all high-paying jobs," O'Neill conceded, "but for the area's young people, it's employment that

wouldn't otherwise be available."

Giving back

A Wharton Business School graduate, Peter Bergum managed some of area's retail landmarks, including the

Cherry Hill Mall, Plymouth Meeting Mall, and the Gallery at Market East. None prepared him for Franklin Mills role as

neighborhood benefactor.

"We would make small charitable donations, but I never had an advisory council and gave money directly to the

community," Bergum said.

Franklin Mills opened in a city drowning in red ink. It not only ceased building recreation centers, but struggled

to maintain those in operation.

Western stepped to the plate.

"It wasn't done out of the goodness of their heart," said a local official. "Those were concessions won in

negotiations with the community."

Nonetheless, the mall spent $1.6 million for two gymnasiums and the new Northeast Senior Citizen Center. It

also provides $29,500 a year (adjusted for inflation every five years) for community projects deemed worthy by the

Franklin Mills Advisory Council.

The council, run by community advocates, has given out over 50 grants- worth over $200,000- within the 19154

zip code.

Auto thief's dream?

After celebrating its first anniversary, Franklin Mills found itself in a public relations quagmire.

During the first full-year of Franklin Mills' operation (Oct. '89 to '90), auto theft in the Eighth Police District rose

a stunning 77 percent, from 560 reported incidents to 1,009.

"They had been fighting over traffic patterns and the senior center and overlooked what normally occurs when a

mall moves into what was for so long an empty lot," said a local city representative. "People panicked without

understanding all the facts."

Buried in the news reports, of the 1,009 incidents, only 200 occurred in the Franklin Mills sector.

The 15th District (covering Frankford, Tacony, and Mayfair) remained the Northeast's car theft capital with

1,279 incidents, a 23 percent increase over the previous year. The Second Police District, home to Roosevelt Mall,

recorded 963 thefts, a 22.4 percent increase.

Urging caution, Capt. James Glenn Jr., then commander of the Northeast Detective Division, blamed the

economic downturn and drug use. "Cars are stolen to exchange for drugs," he told reporters. Inspector William

McDonough, head of the division's uniformed patrol, cited the district's easy access to I-95 and the Turnpike.

"Our percentages were no higher than at other shopping centers in Philadelphia," said Bergum. "Yes, we had

more auto thefts than we wanted. But we were getting an unfair rap from the media. So we took pro-active steps to change

things," steps, argue police officials, that have made their job easier.

Exterior security cameras now monitor the entire 10,000 space parking lot around the clock. "We have

apprehended car thieves, vandals, and people breaking and entering vehicles," Bergum said. "We can even track fights."

Though staffing numbers shift throughout the year, during the holidays as many as 50 guards patrol the mall.

"With their training, equipment, and supervision, they are a major help to us," said Eighth District Capt.

Elizabeth Romanausky. The mall's security chief, Ralph Calaberdino, is a former Philly cop.

The mall is also home to a police mini-station where officers can process suspects. Without it, "every time they

had a retail theft we would have to send in a van and transport (suspects) to Northeast Detectives where everyone might

have to sit for a (long) while. Now they are transferred to the satellite station, where all the paperwork is done," said

Romanausky.

"That saves the police department the money," said O'Neill.

"We made the improvements well-known to the media," said Bergum, "which (proved) an excellent deterrent."

The evidence? From 1991 to 1993, auto theft at the mall dropped 43 percent. In the same period, robbery

dropped 35 percent.

"We know the word is out on the street because we've broken a number of car theft rings," said Bergum. "Many

were caught by our security force, not the police." "I'll match statistics with any of the other malls," said Calaberdino.

According to police sources, Franklin Mills would win the match-up. "It has fewer bodily injury crimes than at

other malls," said a Northeast police official. "The retail theft that occurs does so because the individual stores won't spend

the extra money required to prevent it."

The future

As more outlet centers open using the Mills' motif, Bergum expects the tour business to stabilize, then drop.

"Why travel two hours to this mall when another outlet mall is only a half-hour away?" Bergum said. "It's no

different than what happened to traditional shopping centers 30 years ago."

To counter the expected loss, Franklin Mills has targeted Convention Center clientele and about 95 percent of

Center City and Northeast Philadelphia hotels. On Wednesdays and Saturdays, the mall subsidizes bus runs from two

Center City hotels. For $10, visitors receive round-trip transportation and a coupon book overflowing with discounts.

"It's more than made up for what we lost in the tour bus business," Bergum said.

This year the mall targeted local shoppers through a series of TV ads. "We need to improve our local shopper

frequency," Bergum said.

That will occur, said O'Neill, as people realize the mall is safe, a good neighbor, and an economic engine that

keeps chugging along.

"It stands as a prime example of how to take acres of empty land and build something that attracts busloads of

people from way outside Philadelphia and all that revenue," said Saidel.

|  Go back to the News page

Go back to the News page Please e-mail us with any comments or suggestions

Please e-mail us with any comments or suggestions Go to the News Gleaner Homepage

Go to the News Gleaner Homepage Find out how to reach us

Find out how to reach us